Understanding Repeat Antibiotic Prescribing in the Pandemic: Insights On Health Inequalities

-

Authors:

Diane Ashiru-Oredope

-

Posted:

- Categories:

This article is part of a series: Guest blogs

- Conducting Research Using OpenSAFELY: My Experience of the Co-pilot Service

- High Dose Dexamethasone

- How I use OpenPrescribing in my practice as a GP

- Conducting Research Using OpenSAFELY: My Experience of the Co-pilot Service

- Using electronic health records and open science in the COVID-19 pandemic

- Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on common infections: Treatment Pathways, Antibiotic Prescribing, and Exposure

- Incidence and management of inflammatory arthritis in England before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Updates of OpenSAFELY Research on COVID-19 Therapeutics

- Understanding Repeat Antibiotic Prescribing in the Pandemic: Insights On Health Inequalities

- Trends in inequalities in avoidable hospitalisations across the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped many aspects of healthcare, including how antibiotics are prescribed in primary care settings. In this guest blog, Professor Diane Ashiru-Oredope lead pharmacist for antimicrobial resistance at UK Health Security Agency and our own Brian MacKenna, share some insights on repeat antibiotic prescribing and the link to health inequalities from a recent UK Health Security Agency analysis using OpenSAFELY.

Patient Characteristics Associated with Repeat Antibiotic Prescribing Pre- and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Using too many antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals and antiparasitics can make them less effective, which is why we need to be careful about how they are used due to the threat of “antimicrobial resistance” (AMR). Careful and appropriate usage is known as “antimicrobial stewardship”. An important aspect of antibiotic stewardship is avoiding inappropriate repeat antibiotic prescriptions in primary care, where patients may receive multiple courses of prescriptions over the course of a year either on separate occasions or available for them to reorder without seeing a healthcare professional.

In this study (full text), we use a definition of three or more antibiotic prescriptions in a six month period as a repeat prescription. Overall, we found that antibiotic prescribing decreased during the pandemic, the reasons for this has been highlighted as complex and likely multifactorial including due to restrictions/lockdowns, changes in healthcare delivery and healthcare-seeking behaviour, . This decline was particularly pronounced for non-repeat prescribing, compared with repeat prescribing.

Health Inequalities

Due to the scale of data from general practitioners (GPs) available in OpenSAFELY we were also able to investigate in granular detail the clinical and demographic characteristics of small groups of patients. We found that older patients and care home residents were more likely to receive antibiotics, especially repeat antibiotic prescriptions. In addition, we found the burden of repeat prescribing was highest for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and urinary tract infection.

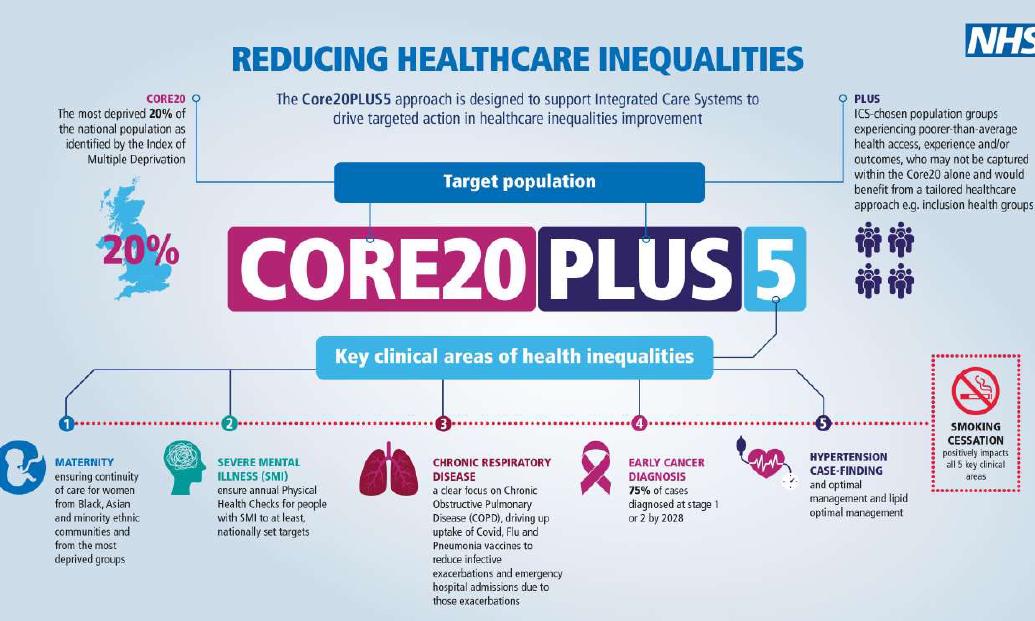

An important part of the OpenSAFELY approach is that all code from every study is openly shared for re-use by all researchers. This made it very easy for us to include analysis on health inequalities. In this study we used the NHS England CORE20PLUS5 approach to analysing health inequalities. Briefly, this is an approach that supports targeting of the most deprived 20% by Index of Multiple Deprivation nationally, PLUS - groups deemed at risk of health inequalities such as those from ethnic minorities,and 5 specific conditions such as COPD. At OpenSAFELY we have made all the code to support re-use available in one place and you can read more in this blog if interested.

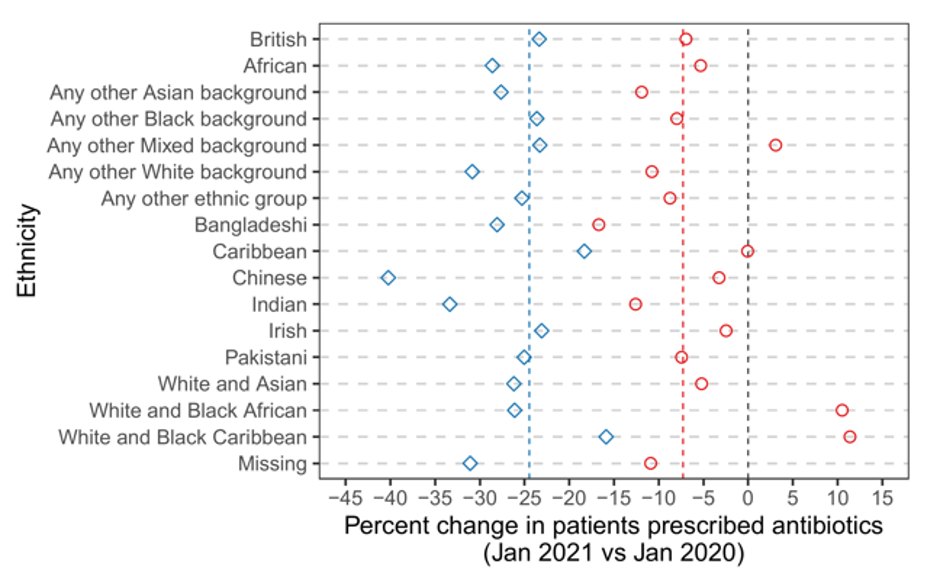

Our published paper has lots of information and breakdowns, but for this blog we will just focus on ethnicity. We believe that this is one of the most granular studies ever of antibiotics prescribing looking at detailed clinical and demographic subgroups. In the figure below below you can see changes in antibiotic prescribing divided into the 16 categories from the UK census. Overall there was a general trend of decreasing repeat and non-repeat antibiotic prescriptions but we are able to see huge variation in the changes across ethnic minorities. Compared to before the pandemic, we saw a much larger drop in single-course antibiotic prescriptions among patients of Chinese ethnicity, with a 40.23% decrease. On the other hand, for people with mixed ethnic backgrounds, such as White and Black African, White and Black Caribbean, and other mixed backgrounds, we actually noticed an increase in repeat prescriptions during the pandemic compared to before. We can also see distinct differences in patterns of prescribing for the between Indian and Pakistani communities, two groups which are normally aggregated together in smaller studies hiding these differences.

Figure 1 Percentage change in the rate of repeat and non-repeat antibiotic prescribing among patients in the January 2021 (pandemic) cohort vs. January 2020 (pre-pandemic) cohort—categorised by ethnicity. The red and blue dashed lines indicate the overall percent change in the rate of repeat and non-repeat prescribing, respectively.

Figure 1 Percentage change in the rate of repeat and non-repeat antibiotic prescribing among patients in the January 2021 (pandemic) cohort vs. January 2020 (pre-pandemic) cohort—categorised by ethnicity. The red and blue dashed lines indicate the overall percent change in the rate of repeat and non-repeat prescribing, respectively.

Why this matters?

These findings are helpful for understanding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic prescribing, impacts on different groups of the population and developing interventions to improve antimicrobial stewardship. The findings from this study was important to identify which areas to focus on for the development of antimicrobial stewardship tools to support general practice. Since the project has completed, we have developed and published two “How to….” resources supporting general practice teams to manage and review adults on long-term and repeated antibiotics for the treatment and prevention of Acne Vulgaris and COPD exacerbations. UKHSA has made both of these resources openly available for everyone to re-use.

Get in touch!

All of the code used for our analyses is open and reusable so that other researchers interested in similar work can readily adopt these methods in their own work. If you have more questions about the research summarised here please get in touch via espaur@ukhsa.gov.uk.

If you are very interested in AMR you might also enjoy the OpenSAFELY blog by the team from the University of Manchester summarising their work on antibiotics.

If you are interested in developing your own studies in OpenSAFELY, NHS England is currently supporting expansion of the OpenSAFELY service and anticipate that new applications will be accepted from early 2024.

Please cite our paper as

Orlek, Alex, Eleanor Harvey, Louis Fisher, Amir Mehrkar, Seb Bacon, Ben Goldacre, Brian MacKenna, and Diane Ashiru-Oredope. 2023. “Patient Characteristics Associated with Repeat Antibiotic Prescribing Pre- and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Nationwide Cohort Study of >19 Million Primary Care Records Using the OpenSAFELY Platform” Pharmacoepidemiology 2, no. 2: 168-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharma2020016